Contents

Abstract

Projector-based augmented reality (AR) enables robots to communicate spatially-situated information to multiple observers without requiring head-mounted displays, e.g., projecting navigation path. However, they require flat and weakly textured projection surfaces; otherwise, the surface needs to be compensated to retain the original projected image. Yet, existing compensation methods assume static projector-camera-surface configurations and may not work in complex, textured environments where robots must navigate.

In this work, we evaluate state-of-the-art deep learning-based projection compensation on a Go2 robot dog in a search-and-rescue scene with discontinuous, non-planar, strongly textured surfaces. We contribute empirical evidence on critical performance limitations of state-of-the-art compensation methods: the requirement of pre-calibration and inability to adapt in real-time as the robot moves, revealing a fundamental gap between static compensation capabilities and dynamic robot communication needs. We propose future directions for enabling real-time, motion-adaptive projection compensation for robot communication in dynamic environments.

CCS Concepts: Computer systems organization → Robotics; • Human-centered computing → Mixed / augmented reality.

Keywords: Projector-robot system, Projector compensation, Projector-camera system, Augmented Reality, Human-Robot Interaction

ACM Reference Format: Hong Wang, Ngoc Bao Dinh, and Zhao Han. 2026. Evaluating Dynamic Surface Compensation for Robots with Projected AR. In Companion Proceedings of the 21st ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI Companion ’26), March 16–19, 2026, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 6 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3776734.3794434

1 Introduction

For robots to work effectively with people, they must be able to communicate task-related information and their intent clearly to gain trust and acceptance. Human-robot interaction (HRI) researchers have traditionally investigated non-verbal means, e.g., gesture [13, 43], eye gaze [1, 36], sound [61], visual display [49], light [3], and verbal speech [50]. However, real-world interactions are highly contextual and often involve specific objects and locations in the physical world. When communicating about spatially situated targets in cluttered scenes, traditional modalities such as gesture, gaze, and speech can lack precision and clarity, while low-fidelity sound and light signals are less expressive, and on-robot displays suffer from limited viewing angles and legibility at a distance.

Figure 1: A robot dog in a search-and-rescue scene with textured and non-flat surfaces, on which projecting requires compensation to correct geometric and photometric distortions. We contribute empirical evidence for state-of-the-art compensation performance.

To enable robots to communicate spatially situated objects, researchers are increasingly leveraging augmented reality (AR) [16, 42, 51, 54, 55]. AR spatially registers 3D virtual content onto the physical world, allowing visualizations to be situated where they are relevant, also known as situated visualization [44]. Applied to robotics, for example, AR allows robots to precisely externalize motion intent, e.g., manipulation and navigation trajectories directly in the task space, e.g., which object it refers to [8, 19], perceived or to be manipulated [42], or which path it will navigate for both ground robots [20] and drones [56]. Results have shown improved safety during navigation, with participants choosing alternative paths [11], increased comfort, and motion intelligence [59]. Recently, AR virtual appendage was even perceived more anthropomorphic [21], activating familiar human-human interaction patterns.

Yet, we risk losing these benefits that AR offers to robotics due to a major scalability issue associated with the popular headset-based AR displays. They require each viewer to wear a headset, which is often impractical for a crowd of people in a group and team context [45]. In contrast, projector-based AR projects augmentation directly onto the scene, viewable to many observers at once. To retain the benefits of AR situated visualization in dynamic environments where robot operates and interacts with humans, there is a critical research gap on how to enable robots to project onto varied surfaces while moving, requiring real-time compensation that adapts to changing viewpoints, surface geometries, and lighting conditions.

In this work, we evaluate state-of-the-art deep learning-based projection compensation method, CompenHR, on a Unitree Go2 robot dog in a complex, search-and-rescue scene (Fig. 1). We contribute both quantitative and qualitative empirical evidence that identifies a critical limitation: existing compensation methods are inherently static and cannot support the real-time, motion-adaptive requirements of mobile robot communication.

Specifically, our contributions are: (1) We recreate a real-world, representative search-and-rescue debris scene as an evaluation testbed with discontinuous, non-planar, strongly textured surfaces. (2) We empirically evaluate CompenHR on a mobile robot platform, combining quantitative image metrics with qualitative visual inspection across multiple viewpoints. (3) We identify a key limitation: viewpoint-specific compensation that fails to generalize as the robot moves, and we outline future research directions toward motion-adaptive and responsive projection compensation.

2 Related Work

Projectors are widely used in many applications, such as interactive entertainment [4, 5, 30, 39], immersive displays [28, 33, 41], and projector-based spatial AR [18, 34, 35, 52]. Compared to head-mounted see-through displays, projector-based spatial AR directly projects onto the environment, making situated visualizations viewable to multiple interactants or bystanders without requiring them to wear headsets or glasses. In HRI, researchers have used projectors to communicate navigation intent by overlaying a mobile robot’s path with lines [10], arrows [10, 12], gradient bands [59], or simple maps [11]. Human-subjects studies show that such projections can improve comfort and perceived motion intelligence [59], lead to safer path choices [11], and increase efficiency and confidence in understanding robot navigation intent [12].

However, these systems typically assume continuously flat, weakly textured surfaces such as floors or walls. In contrast, the present work considers non-continuous, non-planar, textured construction debris as projection surfaces, where compensation becomes crucial for robust communication in realistic environments.

For immersive and accurate visual experiences on such complex surfaces, projector compensation is needed to correct geometric and photometric distortions introduced by surface shape, texture, and illumination, as reviewed in [6, 17]. For geometric correction, many methods project well-defined patterns or markers, such as structured light [15, 48], to estimate surface geometry. Others simplify this process for efficiency by designing specific patterns [29, 32, 37, 60]. Additional approaches incorporate extra sensors, such as infrared (IR) cameras [22] or depth cameras [27, 47], to track surfaces without visible patterns.

For photometric compensation, algorithms typically generate a projector input that compensates for the color and texture of the surface and the photometric environment. They often estimate a color transfer function by projecting additional patterns [2, 7, 14]. Some recent methods jointly address both geometry and photometry, i.e., full compensation, using carefully designed patterns [40, 46]. Building on these ideas, deep learning approaches have been introduced for projector compensation. Early work focused on photometric compensation [24] and was subsequently extended to full compensation [23, 25, 26]. More recently, these methods have been further extended to high-resolution compensation, exemplified by the state-of-the-art CompenHR [57] that this work uses.

For all these methods, however, it is unknown how they perform when deployed on a mobile robot in a realistic debris environment.

3 Method

3.1 State-of-Art Compensation: CompenHR

CompenHR [57] is a state-of-the-art deep learning method for full projector compensation that addresses both geometric and photometric distortions in an end-to-end trainable framework. The goal of projector compensation is to find a compensated projector input image 𝑥* such that when projected onto a textured, non-planar surface and captured by a camera, the result  * matches the desired appearance 𝑥′:

* matches the desired appearance 𝑥′:  *= T(F(𝑥*; 𝑙,𝑠))≈𝑥′ where T denotes geometric warping due to surface shape, F denotes photometric transformation due to surface reflectance properties 𝑠 and lighting 𝑙. CompenHR learns the inverse mapping: 𝑥*= F†(T-1(𝑥′); T-1(

*= T(F(𝑥*; 𝑙,𝑠))≈𝑥′ where T denotes geometric warping due to surface shape, F denotes photometric transformation due to surface reflectance properties 𝑠 and lighting 𝑙. CompenHR learns the inverse mapping: 𝑥*= F†(T-1(𝑥′); T-1( )) where

)) where  is the captured surface image under ambient lighting.

is the captured surface image under ambient lighting.

CompenHR consists of two main components: (1) GANet (short for Attention-based Geometry Correction Network) uses an attention-based grid refinement network to estimate a warping field that corrects geometric distortions caused by non-planar surfaces, and (2) PANet (short for Attention-based Photometric Compensation Network) is used to recover the high-resolution images, employing shuffle operations to correct color and brightness distortions caused by surface texture and material properties.

Potential Problem: Specifically, CompenHR learns compensation parameters for a fixed geometric relationship between the projector, camera, and projection surface. The geometric correction network (GANet) learns a displacement field that transforms the camera view to the projector’s canonical frontal view. This transformation is only valid for the specific viewpoint where the training data was collected. Similarly, the photometric network (PANet) learns surface reflectance and color properties from that viewpoint. When the projector moves to a new position, both the geometric transformation and photometric properties change, but the network has no mechanism to adapt these learned parameters.

This viewpoint-specific design makes CompenHR representative of current state-of-the-art compensation methods: they achieve high quality through learning viewpoint-specific mappings, but this specialization prevents generalization to new viewpoints.

Figure 2: Construction debris projection surface in three views. Top: images showing complex textured surface. Bottom: depth maps (blue: near, red: far) revealing irregular 3D geometry, which challenges compensation robustness when camera position changes.

3.2 Recreating Search and Rescue Scene

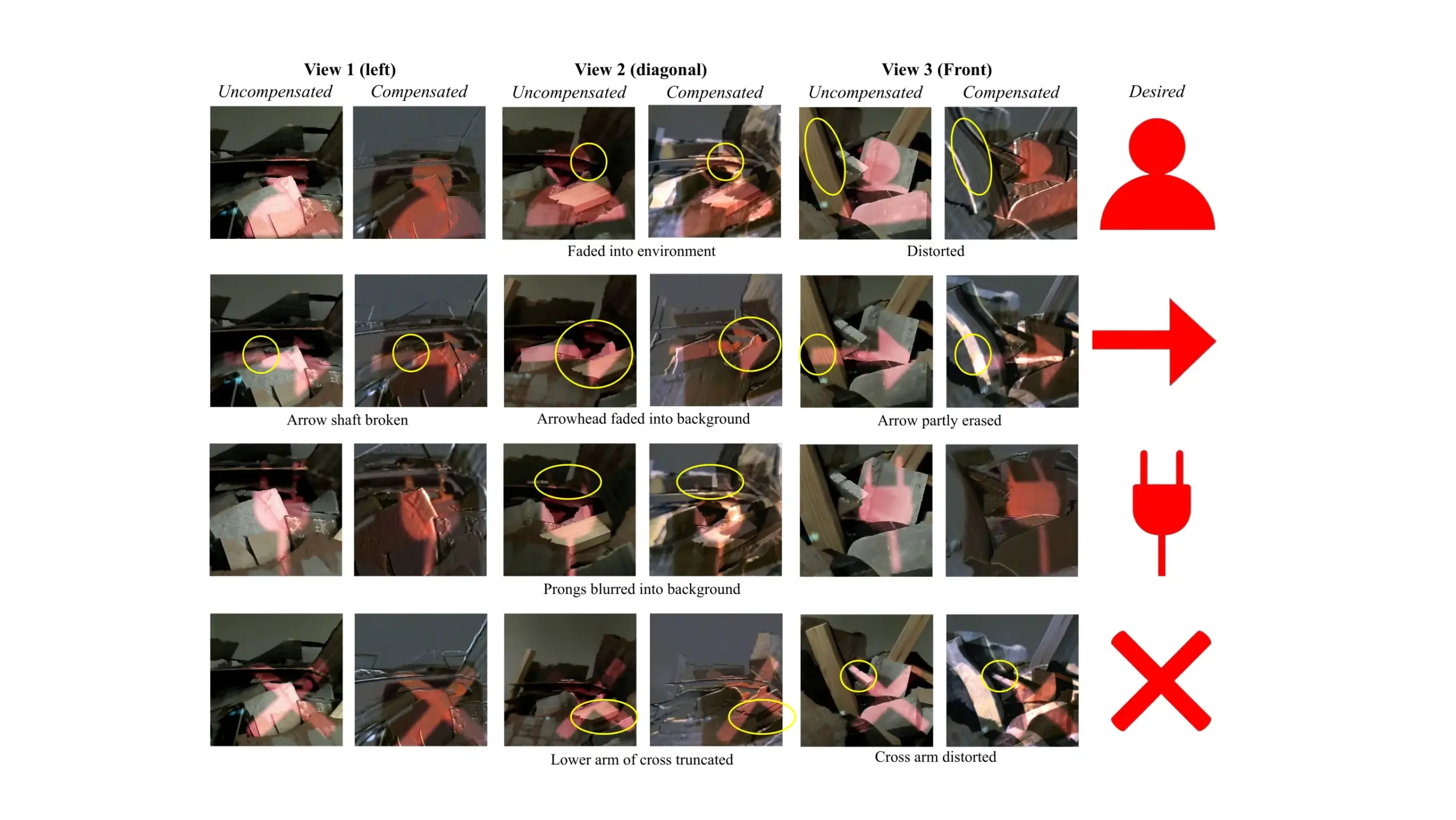

Figure 3: Projector compensation of four different patterns (person, arrow, plug, cross) on construction debris.

Inspired by search-and-rescue missions in Japan, Italy, and the USA at collapsed buildings after earthquakes [9, 31, 38], we constructed a representative disaster scene (Figure 1) for the evaluation. We selected common construction materials: concrete blocks and pavers, asphalt shingles, ceramic tiles, and wooden boards. These materials exhibit diverse reflectance properties, creating realistic photometric conditions with strong textures. We broke the materials to recreate the chaotic geometry of collapse sites while maintaining real-world depth variation (Figure 2 bottom). The resulting surface presents multiple real-world challenges: (1) geometric discontinuities where materials abruptly change depth, (2) strong texture interference from wood grain and shingle patterns, (3) mixed material reflectance requiring different photometric compensation, and (4) occlusions that change depending on viewpoint.

In this real-world scene, we evaluated CompenHR to determine if existing compensation methods can support projection-based communication on a mobile robot in dynamic environments.

3.3 Evaluation Procedure

We tested four typical robot-to-human communication patterns commonly needed in search-and-rescue scenarios with human-robot teaming: a person silhouette (to indicate human detection or survivor presence), a navigation arrow (to show intended navigation path), a plug icon (to indicate low power of the robot), and a cross symbol (to indicate blocked areas).

For each pattern, the Go2 robot projected the image onto the debris field at three different viewpoints of the scene (Figure 2), approximately 0.5 m from the surface at 30◦ elevation angle: View 1 (left): Position near the left side of the debris pile;View 2 (diagonal): Position along the diagonal left side;View 3 (front): Position near the front of the debris pile.

For each viewpoint, we captured the surface image and the uncompensated projection of the pattern, as seen in Figure 3. These camera-captured images were used to generate compensated projections with CompenHR’s pretrained high-resolution model.

Then, for every viewpoint and pattern, we recorded: (1) an uncompensated projection (raw pattern projected directly onto the scene) and (2) a compensated projection (CompenHR output).

Our projector-robot system comprises a Go2 robot dog from Unitree, Go2’s camera [53], and ViewSonic LS711HD, a 4,200-lumen 1080p short throw projector. This forms a similar projector–camera pair to standard ProCams setups but on a moving platform.

4 Results

Table 1: Average image similarity scores between compensated and uncompensated projections across four patterns, quantifying how strongly CompenHR modifies the raw projection at each viewpoint.

| View | PSNR (dB) ↑ | SSIM ↑ | RMSE ↓ |

| View 1 (left) | 13.79 | 0.5171 | 52.14 |

| View 2 (diagonal) | 14.02 | 0.5558 | 51.39 |

| View 3 (front) | 12.71 | 0.5013 | 60.12 |

To characterize how strongly compensation changes the projected image, we compute three standard image similarity metrics between the camera-captured compensated projection and the corresponding uncompensated projection at each viewpoint: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) [58], Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) [58], and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). PSNR summarizes the average pixel-wise intensity error; higher values indicate more similar images. SSIM ranges from 0 to 1 and captures structural similarity (1 denotes identical; values around 0.5 indicate moderate structural agreement). RMSE measures the average per-pixel intensity difference, with larger values indicating stronger deviation. Table 1 shows the aggregated results.

View-dependent photometric change. CompenHR produces substantial photometric changes across all views when comparing compensated to uncompensated projections: PSNR values are in the low 12.7–14.0 dB range and SSIM values are around 0.50–0.56, both indicating notable differences between compensated and uncompensated projections. Views 1 and 2 exhibit similar levels of modification, whereas View 3 shows more aggressive and structurally different changes with the largest RMSE and lowest PSNR/SSIM.

Degradation in symbol structure at different views. These metrics alone do not tell whether compensation improves recognizability with respect to the ideal symbols. Fig. 3 provides qualitative insight. For several patterns, compensation improves symbol contrast or reduces background interference: For example, the arrowhead becomes more distinct at View 2, and the person silhouette becomes more uniformly colored at View 1. However, the same compensation sometimes breaks or distorts key parts of the symbols: arrow shafts become disconnected at View 3, plug prongs blur into the background at View 2, and the cross symbol’s arms or legs appear truncated or bent at both View 2 and 3.

Static compensation limitation. This discrepancy between numerical similarity and visual quality demonstrates a key issue: The learned transformations are optimized for a specific projector-camera-surface configuration. As the robot moves to different views, these fixed transformations cannot adapt to the changed geometric relationships and photometric conditions.

5 Discussion and Future Work

Our evaluation highlights both the promises and the limitations of projector compensation for projected-AR-based robot communication on complex, textured debris surfaces.

On the one hand, the quantitative and visual results suggest that CompenHR can make projected symbols more legible than raw, uncompensated projections, such as the person silhouette and the plug icon at View 1. When the robot is able to pause and project from a known, calibrated pose, static compensation may be sufficient to support simple symbolic communication, such as indicating directions or marking human detections.

On the other hand, the degradation observed at certain viewpoints (notably View 3), where RMSE increases and structural artifacts appear in Fig. 3, reveals a mismatch between current compensation algorithms and the realities of mobile robots. Methods like CompenHR are static: They assume a fixed geometric relationship among projector, camera, and surface, and they learn viewpoint-specific mappings. A mobile robot, however, must communicate while navigating, turning, and repositioning with respect to both humans and the environment. Under these conditions, a one-time calibration and fixed compensation field are not enough. Moreover, image-based metrics such as PSNR, SSIM, and RMSE do not fully capture human-centered outcomes that matter in HRI, such as reliable interpretation of the symbol and recognition efficiency.

Inspired by those needs, we lay out several future directions:

1. Geometric Adaptation with Continuous Tracking. Rather than learning fixed warping fields with a static-world assumption, future methods could track surface geometry continuously using visual markers or SLAM. As the robot moves, the compensation module would retain most of its warping and update it partially based on the new additions of the view, narrowing down the search space while still allowing projections spatially aligned with the environment.

2. Low-latency Photometric Compensation. The CompenHR architecture is computationally heavy and not designed for real-time inference. Future work can explore lightweight photometric models, probably trade some accuracy for significantly reduced latency, targeting update rates compatible with a robot’s movement.

3. Human Evaluation. Finally, user studies are needed to measure how compensation quality, including failures, and update rate affect the interpretation of compensated projections, task performance, and trust. Combining them with objective image metrics will help evaluate different levels of compensation in different HRI scenarios and guide algorithm design toward human-relevant performance.

6 Conclusion

On a mobile robot in a search-and-rescue debris environment, we evaluated state-of-the-art projector-compensation method, CompenHR. Our results show that compensation can improve the recognizability of projected symbols on textured, non-planar surfaces at a calibrated pose, but degrades as the robot moves to new viewpoints. This gap between static compensation and dynamic, real-time communication needs in mobile HRI motivates future work on motion-adaptive, human-centered projection methods.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2529206.

References

[1] Henny Admoni and Brian Scassellati. 2017. Social eye gaze in human-robot interaction: a review. Journal of Human-Robot Interaction 6, 1 (2017), 25–63.

[2] Ryo Akiyama, Taiki Fukiage, and Shin’ya Nishida. 2022. Perceptually-based optimization for radiometric projector compensation. In 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW). IEEE, 750–751.

[3] Kim Baraka. 2016. Effective non-verbal communication for mobile robots using expressive lights. Dissertion, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA (2016).

[4] Oliver Bimber. 2006. Multi-projector techniques for real-time visualizations in everyday environments. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2006 Courses. 4–es.

[5] Oliver Bimber, Andreas Emmerling, and Thomas Klemmer. 2005. Embedded entertainment with smart projectors. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2005 Courses. 8–es.

[6] Oliver Bimber, Daisuke Iwai, Gordon Wetzstein, and Anselm Grundhöfer. 2008. The visual computing of projector-camera systems. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2008 classes. 1–25.

[7] Panagiotis-Alexandros Bokaris, Michèle Gouiffès, Christian Jacquemin, and Jean-Marc Chomaz. 2014. Photometric compensation to dynamic surfaces in a projector-camera system. In European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 283–296.

[8] Landon Brown, Jared Hamilton, Zhao Han, Albert Phan, Thao Phung, Eric Hansen, Nhan Tran, and Tom Williams. 2023. Best of both worlds? combining different forms of mixed reality deictic gestures. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction 12, 1 (2023), 1–23.

[9] Jennifer Casper and Robin R. Murphy. 2003. Human-robot interactions during the robot-assisted urban search and rescue response at the world trade center. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 33, 3 (2003), 367–385.

[10] Ravi Teja Chadalavada, Henrik Andreasson, Robert Krug, and Achim J Lilienthal. 2015. That’s on my mind! robot to human intention communication through on-board projection on shared floor space. In 2015 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR). IEEE, 1–6.

[11] Ravi Teja Chadalavada, Henrik Andreasson, Maike Schindler, Rainer Palm, and Achim J Lilienthal. 2020. Bi-directional navigation intent communication using spatial augmented reality and eye-tracking glasses for improved safety in human–robot interaction. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 61 (2020), 101830.

[12] Michael D Coovert, Tiffany Lee, Ivan Shindev, and Yu Sun. 2014. Spatial augmented reality as a method for a mobile robot to communicate intended movement. Computers in Human Behavior 34 (2014), 241–248.

[13] Jan De Wit, Paul Vogt, and Emiel Krahmer. 2023. The design and observed effects of robot-performed manual gestures: A systematic review. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction 12, 1 (2023), 1–62.

[14] Kensaku Fujii, Michael D Grossberg, and Shree K Nayar. 2005. A projector-camera system with real-time photometric adaptation for dynamic environments. In 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), Vol. 1. IEEE, 814–821.

[15] Jason Geng. 2011. Structured-light 3D surface imaging: a tutorial. Advances in optics and photonics 3, 2 (2011), 128–160.

[16] Thomas Groechel, Zhonghao Shi, Roxanna Pakkar, and Maja J Matarić. 2019. Using socially expressive mixed reality arms for enhancing low-expressivity robots. In 2019 28th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN). IEEE, 1–8.

[17] Anselm Grundhöfer and Daisuke Iwai. 2018. Recent advances in projection mapping algorithms, hardware and applications. In Computer graphics forum, Vol. 37. Wiley Online Library, 653–675.

[18] Takumi Hamasaki, Yuta Itoh, Yuichi Hiroi, Daisuke Iwai, and Maki Sugimoto. 2018. Hysar: Hybrid material rendering by an optical see-through head-mounted display with spatial augmented reality projection. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 24, 4 (2018), 1457–1466.

[19] Jared Hamilton, Thao Phung, Nhan Tran, and Tom Williams. 2021. What’s the point? tradeoffs between effectiveness and social perception when using mixed reality to enhance gesturally limited robots. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction. 177–186.

[20] Zhao Han, Jenna Parrillo, Alexander Wilkinson, Holly A Yanco, and Tom Williams. 2022. Projecting robot navigation paths: Hardware and software for projected ar. In 2022 17th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI). IEEE, 623–628.

[21] Zhao Han, Yifei Zhu, Albert Phan, Fernando Sandoval Garza, Amia Castro, and Tom Williams. 2023. Crossing reality: Comparing physical and virtual robot deixis. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction. 152–161.

[22] Naoki Hashimoto, Ryo Koizumi, and Daisuke Kobayashi. 2017. Dynamic projection mapping with a single IR camera. International Journal of Computer Games Technology 2017, 1 (2017), 4936285.

[23] Bingyao Huang and Haibin Ling. 2019. Compennet++: End-to-end full projector compensation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 7165–7174.

[24] Bingyao Huang and Haibin Ling. 2019. End-to-end projector photometric compensation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 6810–6819.

[25] Bingyao Huang and Haibin Ling. 2021. Deprocams: Simultaneous relighting, compensation and shape reconstruction for projector-camera systems. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 27, 5 (2021), 2725–2735.

[26] Bingyao Huang, Tao Sun, and Haibin Ling. 2021. End-to-end full projector compensation. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 44, 6 (2021), 2953–2967.

[27] Muhammad Twaha Ibrahim, M Gopi, and Aditi Majumder. 2023. Projector-camera calibration on dynamic, deformable surfaces. In 2023 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW). IEEE, 905–906.

[28] Adrian Ilie, Kok-Lim Low, Greg Welch, Anselmo Lastra, Henry Fuchs, and Bruce Cairns. 2004. Combining head-mounted and projector-based displays for surgical training. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 13, 2 (2004), 128–145.

[29] Shingo Kagami and Koichi Hashimoto. 2019. Animated stickies: Fast video projection mapping onto a markerless plane through a direct closed-loop alignment. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 25, 11 (2019), 3094–3104.

[30] Yusuke Kemmoku and Takashi Komuro. 2016. AR tabletop interface using a head-mounted projector. In 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR-Adjunct). IEEE, 288–291.

[31] Geert-Jan M. Kruijff, Fiora Pirri, Mario Gianni, Panagiotis Papadakis, Matia Pizzoli, Arnab Sinha, Viatcheslav Tretyakov, Thorsten Linder, Emanuele Pianese, Salvatore Corrao, Fabrizio Priori, Sergio Febrini, and Sandro Angeletti. 2012. Rescue robots at earthquake-hit Mirandola, Italy: A field report. In 2012 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR). IEEE, 1–8.

[32] Yuqi Li, Niguang Bao, Qingshu Yuan, and Dongming Lu. 2012. Real-time continuous geometric calibration for projector-camera system under ambient illumination. In 2012 International Conference on Virtual Reality and Visualization. IEEE, 7–12.

[33] Aditi Majumder, Duy-Quoc Lai, and Mahdi Abbaspour Tehrani. 2015. A multi-projector display system of arbitrary shape, size and resolution. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2015 emerging technologies. 1–1.

[34] Leo Miyashita, Yoshihiro Watanabe, and Masatoshi Ishikawa. 2018. Midas projection: Markerless and modelless dynamic projection mapping for material representation. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 37, 6 (2018), 1–12.

[35] Yamato Miyatake, Takefumi Hiraki, Daisuke Iwai, and Kosuke Sato. 2021. Haptomapping: Visuo-haptic augmented reality by embedding user-imperceptible tactile display control signals in a projected image. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 29, 4 (2021), 2005–2019.

[36] AJung Moon, Daniel M Troniak, Brian Gleeson, Matthew KXJ Pan, Minhua Zheng, Benjamin A Blumer, Karon MacLean, and Elizabeth A Croft. 2014. Meet me where i’m gazing: how shared attention gaze affects human-robot handover timing. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM/IEEE international conference on Human-robot interaction. 334–341.

[37] Gaku Narita, Yoshihiro Watanabe, and Masatoshi Ishikawa. 2016. Dynamic projection mapping onto deforming non-rigid surface using deformable dot cluster marker. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 23, 3 (2016), 1235–1248.

[38] Francesca Negrello, Alessandro Settimi, Danilo Caporale, Gianluca Lentini, Mattia Poggiani, Dimitrios Kanoulas, Luca Muratore, Emanuele Luberto, Gaspare Santaera, Luca Ciarleglio, Leonardo Ermini, Lucia Pallottino, Darwin G. Caldwell, Nikolaos Tsagarakis, Antonio Bicchi, Manolo Garabini, and Manuel Giuseppe Catalano. 2018. Humanoids at work: The WALK-MAN robot in a postearthquake scenario. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 25, 3 (2018), 8–22.

[39] Kas m Ozacar, Takuma Hagiwara, Jiawei Huang, Kazuki Takashima, and Yoshifumi Kitamura. 2015. Coupled-clay: Physical-virtual 3D collaborative interaction environment. In 2015 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR). IEEE, 255–256.

m Ozacar, Takuma Hagiwara, Jiawei Huang, Kazuki Takashima, and Yoshifumi Kitamura. 2015. Coupled-clay: Physical-virtual 3D collaborative interaction environment. In 2015 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR). IEEE, 255–256.

[40] Hanhoon Park, Moon-Hyun Lee, Byung-Kuk Seo, Jong-Il Park, Moon-Sik Jeong, Tae-Suh Park, Yongbeom Lee, and Sang-Ryong Kim. 2008. Simultaneous geometric and radiometric adaptation to dynamic surfaces with a mobile projector-camera system. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 18, 1 (2008), 110–115.

[41] Ramesh Raskar. 2000. Immersive planar display using roughly aligned projectors. In Proceedings IEEE Virtual Reality 2000 (Cat. No. 00CB37048). IEEE, 109–115.

[42] Eric Rosen, David Whitney, Elizabeth Phillips, Gary Chien, James Tompkin, George Konidaris, and Stefanie Tellex. 2019. Communicating robot arm motion intent through mixed reality head-mounted displays. In Robotics research: The 18th international symposium ISRR. Springer, 301–316.

[43] Allison Sauppé and Bilge Mutlu. 2014. Robot deictics: How gesture and context shape referential communication. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM/IEEE international conference on Human-robot interaction. 342–349.

[44] Dieter Schmalstieg and Tobias Hollerer. 2016. Augmented reality: principles and practice. Addison-Wesley Professional.

[45] Sarah Sebo, Brett Stoll, Brian Scassellati, and Malte F Jung. 2020. Robots in groups and teams: a literature review. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 4, CSCW2 (2020), 1–36.

[46] Marjan Shahpaski, Luis Ricardo Sapaico, Gaspard Chevassus, and Sabine Susstrunk. 2017. Simultaneous geometric and radiometric calibration of a projector-camera pair. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 4885–4893.

[47] Christian Siegl, Matteo Colaianni, Lucas Thies, Justus Thies, Michael Zollhöfer, Shahram Izadi, Marc Stamminger, and Frank Bauer. 2015. Real-time pixel luminance optimization for dynamic multi-projection mapping. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 34, 6 (2015), 1–11.

[48] Masatoki Sugimoto, Daisuke Iwai, Koki Ishida, Parinya Punpongsanon, and Kosuke Sato. 2021. Directionally decomposing structured light for projector calibration. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 27, 11 (2021), 4161–4170.

[49] Daniel Szafir and Danielle Albers Szafir. 2021. Connecting human-robot interaction and data visualization. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction. 281–292.

[50] Stefanie Tellex, Nakul Gopalan, Hadas Kress-Gazit, and Cynthia Matuszek. 2020. Robots that use language. Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems 3, 1 (2020), 25–55.

[51] Yi-Shiuan Tung, Matthew B Luebbers, Alessandro Roncone, and Bradley Hayes. 2024. Workspace optimization techniques to improve prediction of human motion during human-robot collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction. 743–751.

[52] Tatsuyuki Ueda, Daisuke Iwai, Takefumi Hiraki, and Kosuke Sato. 2020. Illuminated focus: Vision augmentation using spatial defocusing via focal sweep eyeglasses and high-speed projector. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 26, 5 (2020), 2051–2061.

[53] Unitree. [n. d.]. About Go2. https://support.unitree.com/home/en/developer#heading-8

[54] Michael Walker, Hooman Hedayati, Jennifer Lee, and Daniel Szafir. 2018. Communicating robot motion intent with augmented reality. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction. 316–324.

[55] Michael Walker, Thao Phung, Tathagata Chakraborti, Tom Williams, and Daniel Szafir. 2023. Virtual, augmented, and mixed reality for human-robot interaction: A survey and virtual design element taxonomy. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction 12, 4 (2023), 1–39.

[56] Michael E Walker, Hooman Hedayati, and Daniel Szafir. 2019. Robot teleoperation with augmented reality virtual surrogates. In 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI). IEEE, 202–210.

[57] Yuxi Wang, Haibin Ling, and Bingyao Huang. 2023. Compenhr: Efficient full compensation for high-resolution projector. In 2023 IEEE Conference Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR). IEEE, 135–145.

[58] Zhou Wang, Alan C Bovik, Hamid R Sheikh, and Eero P Simoncelli. 2004. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE transactions on image processing 13, 4 (2004), 600–612.

[59] Atsushi Watanabe, Tetsushi Ikeda, Yoichi Morales, Kazuhiko Shinozawa, Takahiro Miyashita, and Norihiro Hagita. 2015. Communicating robotic navigational intentions. In 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 5763–5769.

[60] Yoshihiro Watanabe, Toshiyuki Kato, et al. 2017. Extended dot cluster marker for high-speed 3d tracking in dynamic projection mapping. In 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR). IEEE, 52–61.

[61] Brian J Zhang and Naomi T Fitter. 2023. Nonverbal sound in human-robot interaction: a systematic review. ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction 12, 4 (2023), 1–46.